One of the most powerful lessons that I learned from my father was restraint. Holding back can be so much more powerful and effective than brute force. And, learning when to exercise restraint can be one of the most difficult and important lessons in life.

My father had an unmatched way of listening to things that he deemed fruitless. When he decided that there was too much negative energy or that the discussion was no longer productive, he would just say “enough” or “Genug” in Yiddish, he would walk away or he would change the subject. That was it. No disrespect. No harsh words. Just, that we needed to move on. That was his unique way to halt the pointless and divert to the meaningful. We learned to accept and even appreciate it.

That was Aba’s shortcut to restraint. He employed it as a young bachur (Yeshiva student) when others approached his shtender (lectern) in the Beis Medrash (Study Hall) to talk baseball. He used it when we complained incessantly about someone or something. He used it recently when a family member was too verbose about her negative childhood experiences.

While the shortcut “Genug” was his mainstay restraint mechanism, there were memorable times that called for a more creative and deliberated approach to restraint. I will share two stories that illustrate this type of premeditated restraint, a personal recollection from the seventies and one that occurred last winter. I just heard a third story this week about Aba’s restraint in the Beis Medrash that has served as a restraint paradigm for those who witnessed this event.

When I was growing up on the Telshe Yeshiva campus, my friends and I used to ride our bicycles to the library, a distance of about one mile. The library was at the bottom of a steep hill. We would ride down to the library at full throttle, while we would painstakingly walk our bicycles back up the hill with our baskets full of borrowed books.

One week, I took out a book with content that was unsuitable to my upbringing. I found the book compelling as I read it over Shabbos. While I recognized that it was inappropriate, it was captivating. Sometime during the afternoon, I decided to take a break from my reading. I placed the book face down over the back of the sofa and headed to visit one of my friends.

When I returned, the book was gone.

I knew that my father had taken the book. At first, I was furious. How dare my father read my library book? As my initial anger subsided, I considered my punishment. Would Aba scream at me? Would he take away privileges? As time passed, I became less worried about the punishment and more and more ashamed. As much as I tried, I could not block out the image of my father reading the impure words of this book. A flood of embarrassment overtook me. The more I thought about it, the more shame and worry I felt.

What would my father say or do to me? How could I respond? How would I even have this type of conversation with someone whose eyes and heart were so pure?

I waited for my father to return from Shul (Synagogue) after Shabbos. I could barely breathe. My heart was pumping so quickly that I could not even concentrate.

My father finally returned home from Maariv (evening prayer) to recite Havdolah (End of Shabbos Ceremony). He said nothing. Not a word.

He made Havdolah. He enjoyed a short Melave Malka (end of Shabbos meal) with my mother. Still nothing.

My mother left the room and my father called me to a private space. My chest was pounding and I could barely meet his eyes.

My father was calm.

I saw the anguish in his eyes and he saw the fear in my shame.

He said something like, “Please return the book to the library without reading another word. It is not a book befitting someone as dignified as you.” No yelling. No punishment. Just a simple suggestion.

In that moment, I felt relief wash over me. I could redeem myself. I could fix what I had done wrong. And, that was it.

In that brief and touching encounter, I felt Aba’s embrace in his disappointment, his trust in his only daughter overwhelming the anguish.

That evening, I learned about standards. In that encounter, I also earned a lifelong lesson about restraint.

Had Aba admonished me right away, the reprimand would not have been as effective. Had my father yelled at me or punished me, it probably would not have achieved what his calm trust in me accomplished. My father didn’t embarrass me in front of anyone, although he let my conscience do all the work. This type of restraint may have come naturally to him, because he worked on patience and restraint. Looking back, this was a brilliant and effective lesson in life, one that will probably take my entire life to achieve.

The second story is one that I recently heard and it speaks to my father’s restraint in a public scenario. The story is about my ill father’s restraint as he defended an anguished student against his bullies and a system that unknowingly sheltered these tormentors.

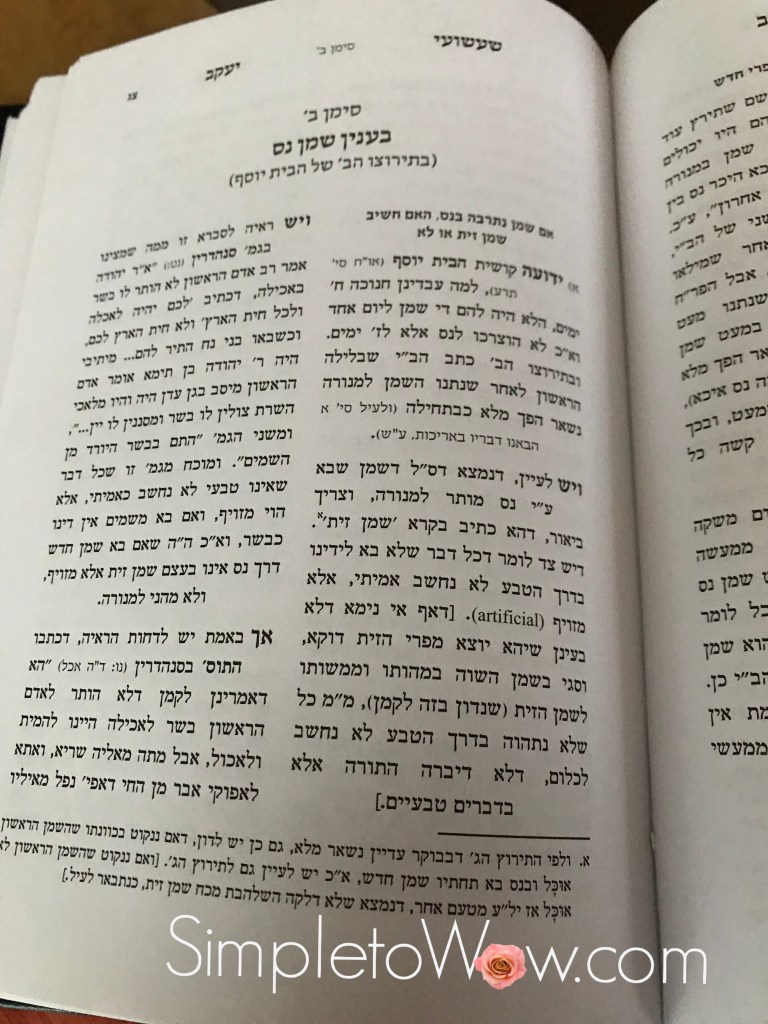

My father was invited to speak at an esteemed Yeshiva. It was shortly before Chanukah and he was excited to share his Torah on Shemen Neis (Miracle Oil). It was a topic that Aba had already prepared and edited for his new sefer and it was one of his favorite lectures. The yeshiva had arranged for him to be driven there to present the forty-minute speech.

On the way, the driver who had great respect for the yeshiva shared an unfortunate incident with my father. It seems that one of his friends had recently sent his son to this elite yeshiva and that the new student was being teased and bullied by some of the older Bocherim. The menacing was so upsetting that the driver’s friend was considering switching his son to another yeshiva.

My father was livid. How could Torah students bully another bachur? How could an Institute of Torah learning support this type of behavior? How is it possible to learn and teach Torah in an environment that is hostile even to one student?

My father verified the bullying claim and once he confirmed its truth, he took matters into his own hands. He asked the driver to detour. Aba needed to pick up notes on a different sugya (topic) called Talmid she’eino hagun (Inappropriate student). It was a topic that he was just completing for his sefer and it was being readied for his chapter on Shavuos and Torah learning. He felt that it would be a more suitable topic for this yeshiva and he was ready to switch gears to teach these boys an unexpected lesson.

The driver desperately tried to dissuade my father from this new diversion. My father refused to be deterred. He was adamant about picking up the new study materials. As much as the driver pleaded with my father, Aba remained firm. He would need the notes on Talmid She’eino Hagun, and that was it. As my father and the driver traveled to pick up the new notes, Aba shared his precise and clear lecture on Talmid She’eino Hagun, elucidating this difficult topic and emphatically proving that a bully is the prime example of an inappropriate student.

The Yeshiva boys were eagerly awaiting my father’s arrival. Using his rollator, my father marched right up to the podium, dismissing all introductions and accolades. Despite the rigors of his chemo and his weakened state, my father calmly and patiently presented the forty-minute lecture. Aba explained all the possibilities of understanding the difficult sugya. He questioned and prodded the students, forcing them to examine the topic in an entirely new way. He included their ideas and built upon the Torah piece, brick by brick.

They were spellbound. The difficult topic with a myriad of different approaches had been presented to them in the clearest way. They had developed the sugya brilliantly and it all seemed so simple. Together, my father and these talmidim (students) had explored Shemen Neis as never before.

The topic illuminated the miracle of Chanukah so dazzlingly. They had discovered brand new insights into the way the oil miraculously burned for the full eight days, while there was only enough oil naturally to burn for one day. Did they pour all the oil into the menorah the first night or did they only use 1/8 of the oil each night? Was the miracle oil actually olive oil? After all, does olive oil need to be from an olive tree or is it possible for a miraculous oil to have the chemical composition of olive oil while not being from a tree at all? Is Shemen Neis olive oil or is it a new substance similar to olive oil? Using a unique combination of sources, my father had mesmerized them with Shemen Neis.

After the long lecture, the students relaxed. They were satiated by the Torah that they had learned. They were enamored with the lecture and the lecturer.

But, my father was only beginning his lesson.

He called the bullied boy to the podium and gently told him that he heard beautiful things about him and his father. A hush overtook the room as the boy left the podium.

“Now fellas. Let me tell you what is more important than the Shemen Neis,” he roared. “Torah may only be learned by someone who is a mentsch, or else your Torah can be a dreadful poison,” he bellowed. “Your Torah and the Torah of your teacher is worth nothing if you boys don’t act properly to one another.”

The students were shocked. Gone was the calm demeanor of the talmid chochom who had just taught them Shemen Neis. Here was the fierce determination of a talmid chochom who was disappointed in their behavior and was defending kovod Ha’Torah (Honor of Torah).

My father now addressed the Rosh Yeshiva, “Here is my sugya on Talmid She’eino Hagun.“ Aba handed the heavy wad of paper to the shocked Rosh Yeshiva and boomed, “Here is the shtickel (piece of) Torah on what I just mentioned. If you have any questions, please call me. ”

That was it. My father had made his point in precisely the way he had planned it. No one could dissuade him from staying true to his principles. He had delivered an entire 40-minute lecture on another topic to whet these boys’ appetites. Aba had earned their respect before he dropped the bomb. He had done it calmly but with conviction. These yeshiva students would never forget this lesson. They were shocked but they accepted the rebuke of my father, dancing him out of the room.

This story was told to me at the shiva. I was enamored by the brilliance and restraint implicit in this story. Once he heard about the bullying incident, I would have thought that my father would choose to first lecture these students on Talmid She’eino Hagun . I can only imagine the restraint that it took for him to complete a long lecture on another topic in his weakened state when he was enraged by the despicable behavior of some of these students. He had clearly done it in precisely this way because he understood the psyche of these students. They needed to respect the Chanukah Torah that they were expecting before they could internalize the more important surprise lesson about their errant behavior.

The third story is one that I just heard a few days ago and it offers a glimpse into Aba’s beautiful conduct in the Telshe Beis Medrash. These stories from the Beis Medrash fill me with great joy and contentment because I was not privy to this part of my father’s life. It helps me depict my father in his favorite spot in this world and catch a glimpse of his interactions and lessons to the current and future Talmidei Chachamim of Telshe Yeshiva.

Aba was a force to be reckoned with in the Beis Medrash. He sat in one of the back rows for over fifty years, never wanting honor, yet disseminating kavod haTorah (honor of Torah) wherever and whenever possible. When he would discover a chiddush (new aspect of Torah), he would run around the massive Beis Medrash, sharing his new dimension in Torah. He was loud, boisterous and unapologetic in his favorite domain.

My father took his responsibility as mashgiach (Spiritual Guide) of the Yeshiva very seriously. While Aba never expected his talmidim to maintain his own rigorous schedule, he expected them to be on time for davening and to invest seriously in their Torah. When a talmid came late regularly or shirked the responsibility for learning Torah, they knew Reb Yankel would hold them accountable.

One day, a talmid was tardy once again to the Beis Medrash and my father confronted him. After davening, my father reprimanded him and explained that it was unbefitting of a serious talmid chochum to be perpetually late to the Beis Medrash. My father was famous for saying “shape up or ship out” and perhaps, he used that expression in this context.

The student was not willing to be chastised by Reb Yankel and escalated the tone and decibel level of this discussion in the back of the Beis Medrash. As the discussion became heated, unbeknownst to my father, the other talmidim started to pay attention. My father stood his ground, explaining why this talmid‘s behavior was unacceptable. The fiery discussion continued and became louder and louder.

In a demeaning voice using inappropriate words that the walls of this Beis Medrash have never heard, the talmid affronted my father personally. He called my father an insulting name that the listeners were shocked to hear, especially in this holy place.

The Beis Medrash walls were holding their breath, waiting for the shoe to drop. Reb Yankel had been personally insulted in the most vulgar way in front of the entire Beis Medrash. Everyone knew that my father had the power and the confidence to throw this talmid out of the Beis Medrash. How would he react?

Aba took his time. He took a few breaths. And, then, in his distinctive voice, he responded. Calmly.

My father simply said something like “I can see that now is not the time to finish this conversation. When you can speak using the right words, we will finish this discussion.” That was it. Aba turned on his heels and went back to learning as if nothing had happened.

This story was told to my brother, Moshe, by a talmid chochom of massive proportion who was a young boy at the time this story took place. He was present that fateful morning and he was deeply affected by the scenario and my father’s amazing self-control in a situation where Aba possessed all the power. He intimated that my father’s self-control has become his paradigm of patience, balance and restraint. Whenever he personally has been tested by someone else in this type of way, he conjures an image of this encounter. He replays the holy reel of my father debating this talmid and then calmly retreating to his holy place of Torah.

Restraint comes in different forms. I watched as my father exercised restraint in precisely the correct way for each circumstance. It is a difficult attribute to master and it takes herculean strength and self-control to assert. For my father, it seemed effortless as he dedicated a lifetime to the development of restraint and self-discipline. He employed it in child-rearing, in teaching his students and as a paradigm for others to follow. For me, the “genuk” shortcut may just have to suffice for right now.