עַ֥ל נַהֲר֨וֹת ׀ בָּבֶ֗ל שָׁ֣ם יָ֭שַׁבְנוּ גַּם־בָּכִ֑ינוּ בְּ֝זׇכְרֵ֗נוּ אֶת־צִיּֽוֹן׃ עַֽל־עֲרָבִ֥ים בְּתוֹכָ֑הּ תָּ֝לִ֗ינוּ כִּנֹּרוֹתֵֽינוּ׃ כִּ֤י שָׁ֨ם שְֽׁאֵל֪וּנוּ שׁוֹבֵ֡ינוּ דִּבְרֵי־שִׁ֭יר וְתוֹלָלֵ֣ינוּ שִׂמְחָ֑ה שִׁ֥ירוּ לָ֝֗נוּ מִשִּׁ֥יר צִיּֽוֹן׃ אֵ֗יךְ נָשִׁ֥יר אֶת־שִׁיר־ה’ עַ֝֗ל אַדְמַ֥ת נֵכָֽר׃ אִֽם־אֶשְׁכָּחֵ֥ךְ יְֽרוּשָׁלָ֗͏ִם תִּשְׁכַּ֥ח יְמִינִֽי׃ תִּדְבַּֽק־לְשׁוֹנִ֨י ׀ לְחִכִּי֮ אִם־לֹ֢א אֶ֫זְכְּרֵ֥כִי אִם־לֹ֣א אַ֭עֲלֶה אֶת־יְרוּשָׁלַ֑͏ִם עַ֝֗ל רֹ֣אשׁ שִׂמְחָתִֽי׃ זְכֹ֤ר ה’ ׀ לִבְנֵ֬י אֱד֗וֹם אֵת֮ י֤וֹם יְֽר֫וּשָׁלָ֥͏ִם הָ֭אֹ֣מְרִים עָ֤רוּ ׀ עָ֑רוּ עַ֝֗ד הַיְס֥וֹד בָּֽהּ׃ בַּת־בָּבֶ֗ל הַשְּׁד֫וּדָ֥ה אַשְׁרֵ֥י שֶׁיְשַׁלֶּם־לָ֑ךְ אֶת־גְּ֝מוּלֵ֗ךְ שֶׁגָּמַ֥לְתְּ לָֽנוּ׃ אַשְׁרֵ֤י ׀ שֶׁיֹּאחֵ֓ז וְנִפֵּ֬ץ אֶֽת־עֹלָלַ֗יִךְ אֶל־הַסָּֽלַע׃ {פ}

(Psalms 137)

Upon the rivers of Babylon, there we sat and wept when we remembered Zion. Upon the willows within, we retired our harps. Because there, our captors asked us for words of song and joyous music played with our instruments. “ Sing from the songs of Zion”, they taunted.

How can we sing God’s song in a foreign land? If I forget you, Jerusalem, then let my right hand shrivel. Let my tongue adhere to my palate if I do not remember you [and] if I do not elevate Jerusalem above my highest joy.

Remember God, [to repay] the children of Edom, the day of Jerusalem, when they said: demolish! demolish! to its very foundations. Cruel daughter of Babylon, praised is the one who avenges your treatment of us. Praised is one who seizes and holds your infants against the rock.

This psalm attributed to Jeremiah is sung before the Grace after Meals. After Nebuchadnezzar’s siege of Jerusalem in 597 BCE, the Jewish people were taken to Babylon, where they were held hostage. It expresses the sadness and resolve of our nation as they sat on the shores of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In nine verses, it depicts our yearning for Jerusalem and our determination to avenge the physical and emotional scars inflicted by our enemy.

Although this psalm is most often recited during the three summer weeks of mourning for the Temple, it is particularly poignant now. It expresses the sadness and devastation of a nation who has been massacred physically and psychologically. It depicts a cruel enemy who has violated our people, trying to break our spirit. Iit characterizes an adversary who, after slaughtering our people, torments us with our own music. Yet, it ends with hope for future triumph.

And, this psalm reflects a time where we were deported as a nation to the banks of another country, leaving our beloved Jerusalem behind. We were tormented with our own music, tempting us to retire the melodies of the Jewish Nation. Although beaten down and provoked, we rose to the challenge of the exile to Babylonia, where our nation learned to flourish, learn Torah and create the venerable opus of Oral Jewish Law, the Talmud.

Today, Jewish history repeats itself in the hatred by our enemies, the slaughter, the call for extermination and the desire to snuff out the rhythmic music of our lives. Yet, we have not retired our musical instruments. Our music and dancing propels our nation forward, even as we are reeling from the cruel onslaught of our enemy.

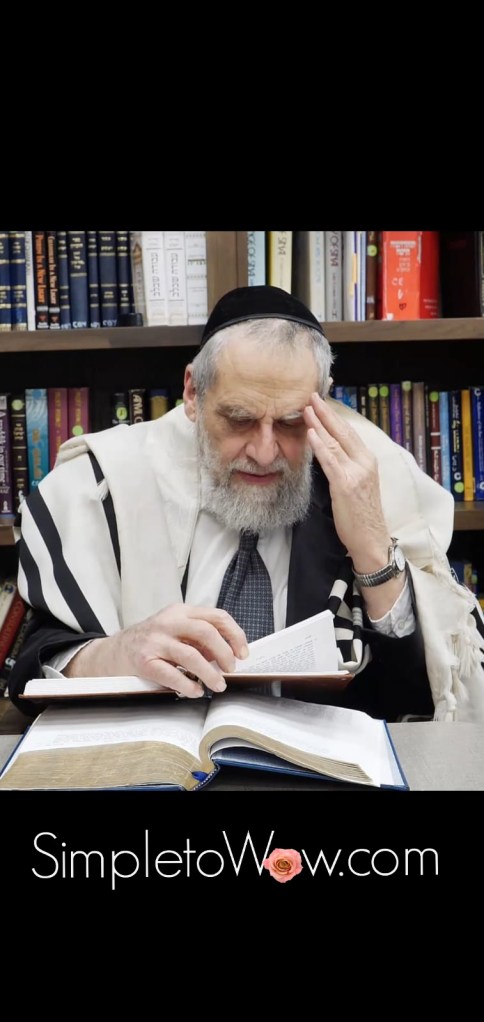

Tonight is the third yahrzeit of my dear and holy father ztL. My father was a paradigm of Torah learning and teaching, a humble and optimistic person much like Rabbi Akiva who laughed when others cried. He was one who sang as he studied Torah, dancing with his talmidim through the joys of finding chidushim (new Torah ideas) and the travails of his final illness. Would my father cry today as the Jewish hostages did on the banks of Babylonia? Would he retire his Torah melody?

My father would understand the horrors of recent history and with the most genuine pain, he would sigh, sharing in the pain and suffering of his brothers and sisters. Then, he would turn to the rhythm and melody of his own life, scrutinizing the words of the Tehillim for hope and inspiration. He would hum as he would poke and prod, evaluating each word until he distilled out the simple truth. He would frame this with the understanding that all God does must be good, even when we are blinded with pain and darkness.

Through the horror and the painful losses, my father would remind me that there is so much to be thankful for. We have not been thrown out of our beloved land, pining for Jerusalem as King David, the psalmist depicts. We have the resolve of a unified, hopeful nation to subdue the enemy. And, our music has only begun.

I have told my children countless times that Jerusalem is a gift given by God to their generation. While I was born before Jerusalem was bestowed upon our nation, my children were born in a time that Jerusalem is ours and that is something to appreciate and never forget.

We have scores of hostages that have been taken into Gaza and we mourn the losses of civilians and soldiers. Our hearts break with each passing day that our hostages are not home and yet, as a people, we are not sitting on the banks of a foreign land. We are in our cherished country with an army to protect us from further onslaught and to avenge the massacre and cruelty. We have troops that pray, sing and dance in unison before entering battle and upon returning from danger-fraught missions.

While my father is in the עולם האמת (World of Truth) and he may be privy to why this devastating period in our history is good, we have the tools to frame the horrors through the words of this psalm, too. We can choose to sing the melody of our lives in the South, in the North, in Gaza and wherever we are. Our enemies can never take that from us.

Furthermore, the psalm describes “retiring our harps among the willows”. The significance of the willows is incredible. October 7th took place on Simchas Torah. In Israel, that was the day after Hoshanah Raba, the seventh day of Sukkos and the final day of divine judgment.

On Hoshanah Raba, we took a bundle of five willows, the simplest of the four species that we gathered for Sukkos. We beat the willow bundle to the ground, We prayed and learned Torah, allowing the lowly willow to avenge our sins. This year, I saved a few leaves from my willow bundle and tucked them into my wallet to remember the aura of Hashanah Rabbah, never imagining what would follow the very next day.

While Hoshana Rabba is a serious day, it is followed with Simchas Torah, a joyful day of song and dancing with the Torah. This Simchas Torah was different as the air raid sirens blasted throughout our Simchas Torah in Jerusalem. While we didn’t yet understand the magnitude of the assault on our nation, we sensed that something terrible was happening. And, in our precious Jerusalem, we continued to sing and dance on that day, saying Tehillim throughout the day and praying for my father’s neshoma at Yitzkor.

Perhaps, the willows represent the connection to the past, the connection of a day of massacre to a day of holy judgment. Perhaps, the lowly willow that grows near the water reminds us of our everlasting song of Torah, represented by water. Perhaps, it is a reminder that even when we are beaten down like the bundle of willows, we will find our melody once again.

We will not hang up our musical instruments. We will sing, we will dance and we will continue the melody that my father and generations before him began. It is the melody of truth and of optimism. It is the melody of Torah and of unity. That will never be taken from us and this time our melody will be stronger, clearer and more beautiful than ever.